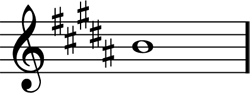

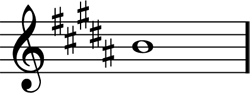

Major Key signatures

C

F

Bb

Eb

Ab

Db

Gb

Cb

G

D

A

E

B

F#

C#

Keys: Locking notes into place,

Scales: a collection of notes used to create melodies in the chosen tonality, and other horizontal lines

Chords: vertical alignment and tonality combined

A key is a set of signs that lock changes to notes into place. We collect all the sharps/flats together at the start of each line into a primer or key signature. This lets us know at a glance all of the notes which are altered during a piece or section. We name each key signature according to its corresponding major scale because different collections of sharps/flats represent different major scales.

C

F

Bb

Eb

Ab

Db

Gb

Cb

G

D

A

E

B

F#

C#

The major scale, regardless of starting note, always has the same pattern of T(ones or Whole Tones) and S(emitones or Half-Tones):

T~T~S~T~T~T~S

C Major Scale

We number each note in the scale from 1 to 8 and give each note within the scale a special name:

| Note # | Name |

|---|---|

| 1 | tonic |

| 2 | super-tonic |

| 3 | mediant |

| 4 | sub-dominant |

| 5 | dominant |

| 6 | sub-mediant |

| 7 | leading tone |

| 8 | tonic (octave) |

We use these names to identify particular notes or chords when we wish to talk about the general use of notes within a key.

Maintaining the pattern, T~T~S~T~T~T~S, regardless of starting note, leads to the introduction of sharps or flats into a scale.

In writing the major scale based on G, the following is initially written:

(a)

Notice the end of example (a) where the pattern fails. Above the notes are a set of arrows that show the changes that need to be made to achieve the correct pattern. We need to move the seventh and eighth notes closer together, whilst also moving the sixth and seventh notes further apart. Example (b) shows the result of making the second last note higher or sharper.

(b)

In writing the major scale based on F, the following is initially written:

(c)

Notice the middle of example (c) where the pattern fails. Above the notes are a set of arrows that show the changes that need to be made to achieve the correct pattern. We need to move the third and fourth notes closer together, whilst also moving the fifth and fourth notes further apart. Example (d) shows the result of making the fourth note lower or flatter.

(d)

When creating a major scale on a given note, you need to ask yourself "to maintain the pattern of the major scale,

Then draw the arrows above the notes to check the direction the note needs to be altered; if the middle pair of arrows point up then sharpen the note, if the middle pair of arrows point down then flatten the note.

One of the more useful features of the major scale is the tendency of the seventh tone to always rise to the octave and the tendency of the fourth tone to always fall to the third tone. When we come to look at Dominant 7th harmony, the utility of these two tendency tones will become apparent.

C Major

G Major

D Major

A Major

E Major

B Major

F# Major

C# Major

C Major

F Major

Bb Major

Eb Major

Ab Major

Db Major

Gb Major

Cb Major

Chords are simply built above the notes of the scale. We start by writing the basic major scale:

We then add the same scale, starting on the third note of the scale, above the initial scale (should sound familiar to those who remember RugRats):

We then add the same scale, this time starting on the fifth note of the scale, above the previously joined scales:

With these three notes per chord, we have the basis of all harmony in the key of the bottom major scale. Chords are known as being major, minor, augmented, or diminished. In the above chord scale, major, minor and diminished chords exist: they can be found as follows:

Notice that all the major chords have the same interval structure: Major third above the bottom note, known as the root note, and a perfect fifth above the root note.

All the minor chords also have the same interval structure: minor third above the root and a perfect fifth above the root also.

The diminished chord consists of a minor third above the root with a diminished fifth above the root.

C Major chords

G Major chords

D Major chords

A Major chords

E Major chords

B Major chords

F# Major chords

C# Major chords

C Major chords

F Major chords

Bb Major chords

Eb Major chords

Ab Major chords

Db Major chords

Gb Major chords

Cb Major chords

Check this for yourself:

To distinguish a chords function (how it works in the scale it comes from); we identify them using Roman numerals.

Using these rules, we can identify the chords built above the major scale as follows:

Sometimes major chords are said to be a major third plus a minor third stacked above each other. In the same way, minor chords are said to be a minor third plus a major third stacked above each other. The same applies to diminished chords: two minor thirds stacked above each other.

In each case, this approach ignores the fifth above the root, leading to difficulties in recognising and understanding later concepts such as altered fifths and chord extensions to the 7th, 9th and 13th.

If you look at every other chord built on the major scale, you will notice that they share two notes with the chords above and below them:

These chords are said to be related, because they share common tones. The related minor chord to the tonic chord of the major scale is the chord built above the sixth note of the scale (the mediant), or chord vi. As a result, we can also talk about the relative minor for any major scale: this is named according to the sixth note of the Major scale. In the case of C Major, this makes the relative minor, A minor.

Next time: